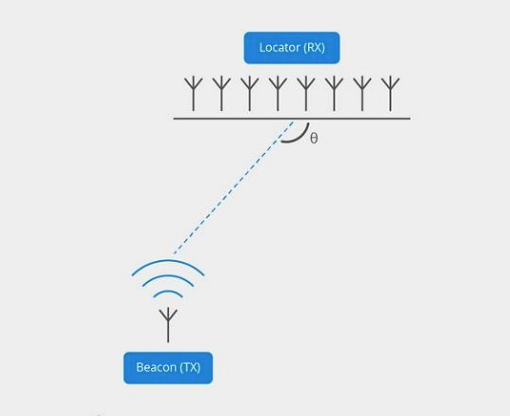

We’ve had several customers express interest in developing their own Angle of Arrival (AoA) software, often starting with basic AoA scripts provided by evaluation boards. Unfortunately, these evaluation scripts are usually insufficient for production-level implementations due to a number of critical limitations.

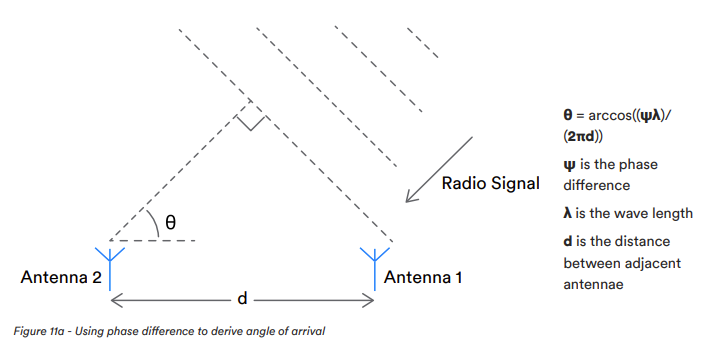

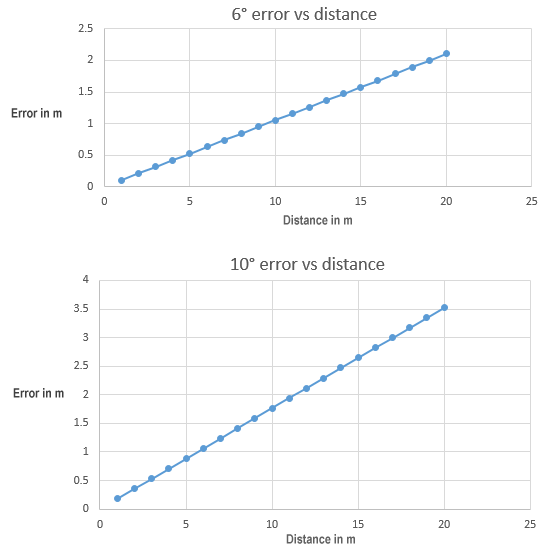

Evaluation board scripts typically apply basic signal processing techniques that struggle with real-world challenges, especially in areas like noise reduction and calibration. Multipath, that’s signals reflecting and arriving in multiple directions, mitigation is often inadequate, making these scripts less effective in complex environments. Simple scripts usually employ straightforward phase interferometry methods that are limited in their ability to handle multipath scenarios. Additionally, they tend to use outdated AoA IQ-to-Angle algorithms, which further affects performance.

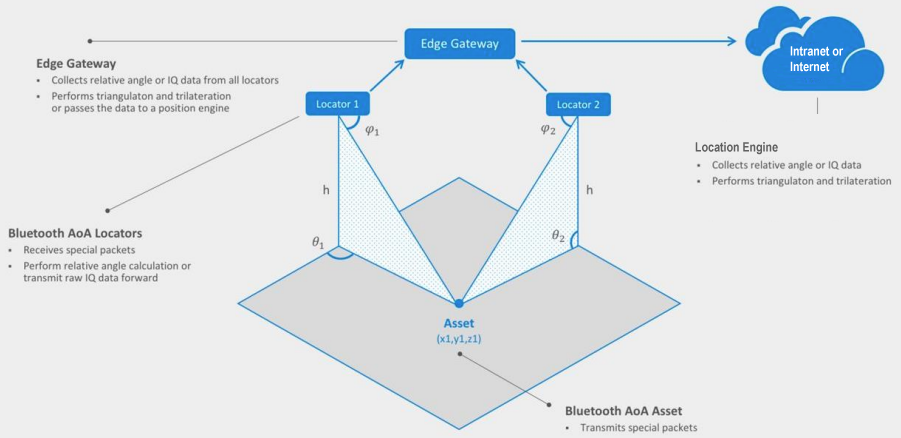

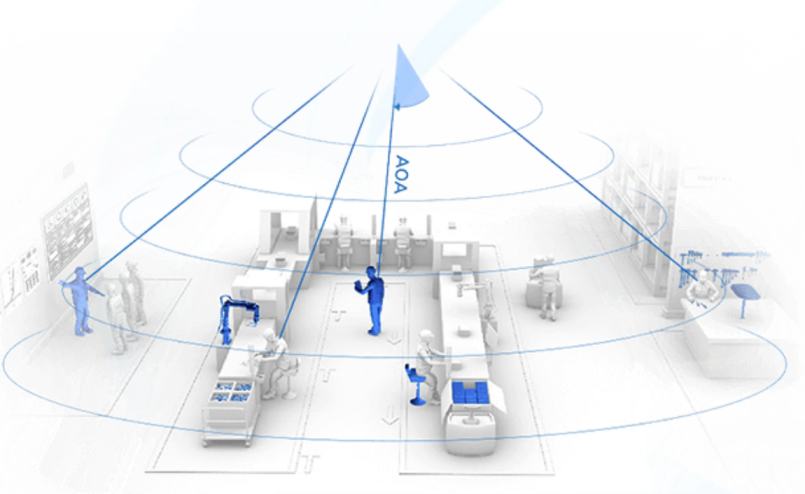

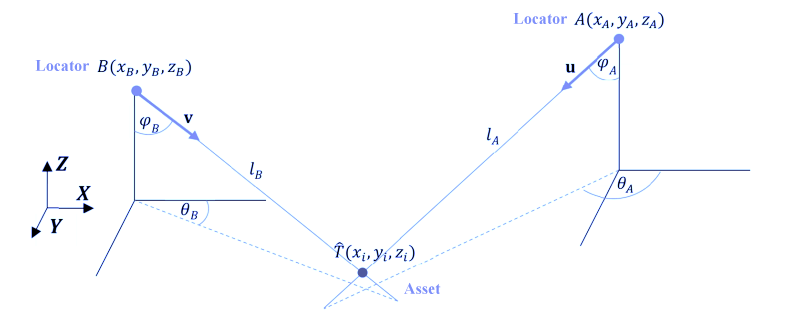

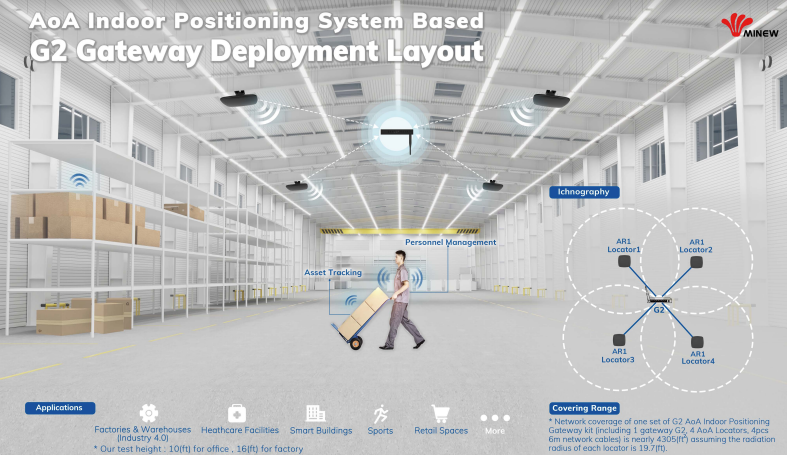

Production systems must be capable of managing multiple tags and anchors simultaneously, in real time. Evaluation scripts, however, are generally designed for a single tag and anchor, lacking the logic necessary for multi-device scenarios. They also don’t include advanced features like parallel processing, trilateration or data fusion across multiple anchors, which are essential for achieving 3D positioning.

Evaluation scripts are also designed for controlled conditions, with minimal error checking. They typically lack robust error detection and correction mechanisms essential for reliability in dynamic environments. Furthermore, these scripts do not incorporate fallback mechanisms, such as temporarily lowering accuracy in the presence of short-term radio frequency noise.

A production-ready system also requires integration with broader ecosystems, such as APIs or interfaces for asset management systems or databases, enabling seamless data flow and operational integration.

Key Areas to Address for Production-Ready AoA Systems:

- Advanced Signal Processing: Noise reduction is essential for ensuring accuracy in challenging environments.

- Multipath Resolution Algorithms: Needed to distinguish direct signals from reflections, enhancing positional accuracy.

- Multi-Device Management: Simultaneously support multiple tags and anchors to enable scalability in deployment.

- Data Fusion and Trilateration: Combine data from multiple anchors to calculate precise 3D positioning.

- Robust Error Handling: Implement comprehensive error detection, logging, correction and fallback mechanisms for consistent reliability.

- Performance Optimisation: Achieve real-time processing by optimising code and utilising hardware acceleration.

- System Integration: Enable compatibility with enterprise systems by providing appropriate interfaces and data formats.

By addressing these areas, a production-ready AoA system can achieve the reliability, accuracy, and scalability required for effective deployment in complex, real-world environments.